Drawing on the British Pathé archive, Seumas Milne picks out the recurrent themes of imperial efforts to control the Middle East

Carved into artificial states after the first world war, it's been bombed and occupied – by the US, Israel, Britain and France – and locked down with US bases and western-backed tyrannies. As the Palestinian blogger Lina Al-Sharif tweeted on Armistice Day this year, the "reason World War One isn't over yet is because we in the Middle East are still living the consequences".

The Arab uprisings that erupted in Tunisia a year ago have focused on corruption, poverty and lack of freedom, rather than western domination or Israeli occupation. But the fact that they kicked off against western-backed dictatorships meant they posed an immediate threat to the strategic order.

Since the day Hosni Mubarak fell in Egypt, there has been a relentless counter-drive by the western powers and their Gulf allies to buy off, crush or hijack the Arab revolutions. And they've got a deep well of experience to draw on: every centre of the Arab uprisings, from Egypt to Yemen, has lived through decades of imperial domination. All the main Nato states that bombed Libya, for example – the US, Britain, France and Italy – have had troops occupying the country well within living memory.

If the Arab revolutions are going to take control of their future, then, they'll need to have to keep an eye on their recent past. So here are seven lessons from the history of western Middle East meddling, courtesy of the archive of Pathé News, colonial-era voice of Perfidious Albion itself.

1. The west never gives up its drive to control the Middle East, whatever the setbacks

Take the last time Arab states started dropping out of the western orbit – in the 1950s, under the influence of Nasser's pan-Arabism. In July 1958, radical Iraqi nationalist army officers overthrew a corrupt and repressive western-backed regime (sounds familiar?), garrisoned by British forces.The ousting of the reliably pliant Iraqi monarchy threw Pathé into a panic. Oil-rich Iraq had become the "number one danger spot", it warned in its first despatch on the events. Despite the "Harrow-educated" King Faisal's "patriotism" – which "no one can question", the voiceover assures us – events had moved too fast, "unfortunately for western policy".

But within a few days – compared with the couple of months it took them to intervene in Libya this year – Britain and the US had moved thousands of troops into Jordan and Lebanon to protect two other client regimes from Nasserite revolt. Or, as Pathé News put it in its next report, to "stop the rot in the Middle East".

Nor did they have any intention of leaving revolutionary Iraq to its own devices. Less than five years later, in February 1963, US and British intelligence backed the bloody coup that first brought Saddam Hussein's Ba'athists to power.

Fast forward to 2003, and the US and Britain had invaded and occupied the entire country. Iraq was finally back under full western control – at the cost of savage bloodletting and destruction. It was the strength of the Iraqi resistance that ultimately led to this week's American withdrawal – but even after the pullout, 16,000 security contractors, trainers and others will remain under US command. In Iraq, as in the rest of the region, they never leave unless they're forced to.

2. Imperial powers can usually be relied on to delude themselves about what Arabs actually think

Could the Pathé News presenter – and the colonial occupiers of the day – really have believed that the "thousands of Arabs" showering petrified praise on the fascist dictator Mussolini as he drove through the streets of Tripoli in the Italian colony of Libya in 1937 actually meant it? You wouldn't guess so to look at their cowed faces.No hint from the newsreel that a third of the population of Libya had died under the brutality of Italian colonial rule, or of the heroic Libyan resistance movement led by Omar Mukhtar, hanged in an Italian concentration camp. But then the "mask of imperialism" the voiceover describes Mussolini as wearing fitted British politicians of the time just as well.

And Pathé's report on the Queen's visit to the British colony of Aden (now part of Yemen) a few years later was eerily similar, with "thousands of "cheering loyal subjects" shown supposedly welcoming "their own Queen" to what she blithely describes as an "outstanding example of colonial development".

So outstanding in fact that barely a decade later the South Yemeni liberation movements forced British troops to evacuate the last outpost of empire after they had beaten, tortured and murdered their way through Aden's Crater district: one ex-squaddie explained in a 2004 BBC documentary on Aden that he couldn't go into details because of the risk of war crimes prosecutions.

A British soldier seizes a demonstrator in Aden's Crater district in 1967. Photograph: Terry Fincher/Getty But then it's far easier to see through the propaganda of other times and places than your own – especially when delivered by preposterous 1950s-style Harry Enfield/Cholmondley-Warner characters.

A British soldier seizes a demonstrator in Aden's Crater district in 1967. Photograph: Terry Fincher/Getty But then it's far easier to see through the propaganda of other times and places than your own – especially when delivered by preposterous 1950s-style Harry Enfield/Cholmondley-Warner characters. The neocons famously expected a cakewalk in Iraq and early US and British coverage of the invasion still had Iraqis throwing flowers at invading troops when armed resistance was already in full flow. And UK TV reports of British troops "protecting the local population" from the Taliban in Afghanistan can be strikingly reminiscent of 1950s newsreels from Aden and Suez.

Even during this year's uprisings in Egypt and Libya, western media have often seen what they wanted to see in the crowds in Tahrir Square or Benghazi – only to be surprised, say, when Islamists end up calling the shots or winning elections. Whatever happens next, they're likely not to get it.

3. The Big Powers are old hands at prettifying client regimes to keep the oil flowing

When it comes to the reactionary Gulf autocracies, to be fair, they don't really bother. But before the anti-imperialist wave of the 1950s did for a slew of them, the British, French and Americans worked hard to dress up the stooge regimes of the time as forward-looking constitutional democracies.Sometimes that effort came rapidly unstuck, as this breezy report on Libya's "first major test of democracy" under the US-British puppet king Idris makes no effort to conceal.

The brazen rigging of the 1952 elections against the Islamic opposition sparked rioting and all political parties were banned. Idris was later overthrown by Gaddafi, oil nationalised and the US Wheelus base closed – though today the king's flag is flying again in Tripoli with Nato's assistance, while western oil companies wait to collect their winnings.

Elections were also rigged and thousands of political prisoners tortured in 1950s Iraq. But so far as British officialdom – entrenched as "advisers" in Baghdad and their military base at Habbaniya – and the newsreels shown in British cinemas at the time were concerned, Faisal's Iraq was a benign and "go-ahead" democracy.

Under the watchful eyes of the US and British ambassadors and "Mr Gibson" of the British Iraq Petroleum Company, we see the Iraqi prime minister, Nuri Said, opening the Zubair oilfield near Basra in 1952 to bring "schools and hospitals" through the "joint labour of east and west".

In fact that would only happen when oil was nationalised – and six years later Said was killed on the streets of Baghdad as he tried to escape dressed as a woman. Half a century on and the British were back in control of Basra, while today Iraqis are battling to prevent a new takeover of their oil in a devastated country US and British politicians again like to insist is a democracy.

Any "Arab spring" state that ditches self-determination for the west's embrace can of course expect a similar makeover – just as client regimes that never left its orbit, such as the corrupt police state of Jordan, have always been hailed as islands of good government and "moderation".

4. People in the Middle East don't forget their history – even when the US and Europe does

The gap could hardly be wider. When Nasser's former information minister and veteran journalist Mohamed Heikal recently warned that the Arab uprisings were being used to impose a new"Sykes-Picot agreement" – the first world war carve-up of the Arab east between Britain and France – Arabs and others in the Middle East naturally knew exactly what he was talking about.

It has shaped the entire region and its relations with the west ever since. But to most non-specialists in Britain and France, Sykes-Picot might as well be an obscure brand of electric cheese-grater.

The same goes for more than a century of Anglo-American interference, occupation and anti-democratic subversion against Iran. British media expressed bafflement at popular Iranian hostility to Britain when the embassy in Tehran was trashed by demonstrators last month. But if you know the historical record, what could be less surprising?

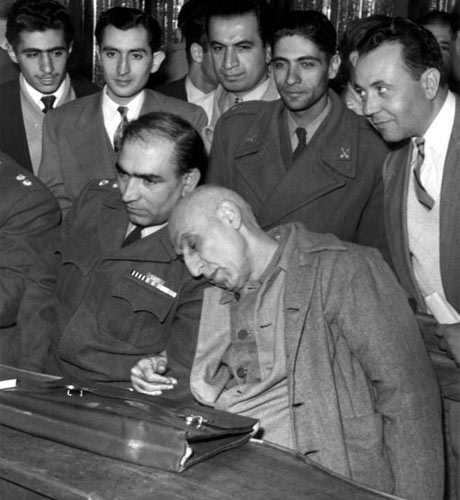

The Orwellian cynicism of Britain's role is neatly captured in Pathé's take on the 1953 overthrow of the democratically elected Iranian leader Mohammed Mossadegh after he nationalised Iran's oil.

Pro-Mossadegh demonstrators are portrayed as violent and destructive, while the violent CIA-MI6 organised coup that ousted him in favour of the Shah is welcomed as a popular and "dramatic turn of events". The newsreel damns as a "virtual dictator" the elected Mossadegh, who at his subsequent treason trial expressed the hope that his fate would serve as an example in "breaking the chains of colonial servitude". The real dictator, the western-backed Shah whose brutal autocracy paved the way for the Iranian revolution and the Islamic Republic 26 years later, is hailed as the people's sovereign.

Mohammed Mossadegh, Iran's ousted prime minister, during his trial in the wake of the CIA-MI6 orchestrated coup that overthrew his elected government in 1953. Photograph: AFP So when western politicians rail against Iranian authoritarianism or claim to champion democratic rights while continuing to prop up a string of Gulf dictatorships, there won't be many in the Middle East who take them too seriously.

Mohammed Mossadegh, Iran's ousted prime minister, during his trial in the wake of the CIA-MI6 orchestrated coup that overthrew his elected government in 1953. Photograph: AFP So when western politicians rail against Iranian authoritarianism or claim to champion democratic rights while continuing to prop up a string of Gulf dictatorships, there won't be many in the Middle East who take them too seriously.5. The west has always presented Arabs who insist on running their own affairs as fanatics

The revolutionary upheaval that began last December in Sidi Bouzid is far from being the first popular uprising against oppressive rule in Tunisia. In the 1950s the movement against French colonial rule was naturally denounced by colonial governments and their supporters as "extremist" and "terrorist".Pathé News certainly had no truck with their campaign for independence. In 1952, it blamed an attack on a police station on a "burst of nationalist agitation" across North Africa. And as colonial police conduct a "vigorous search for terrorists" – though the bewildered men being dragged from their homes at gunpoint look more like Captain Renault's "usual suspects" in Casablanca – the presenter complains that "once again fanatics intervene and make matters worse".

He meant the Tunisian nationalists, of course, rather than the French occupation regime. Arab nationalism has since been eclipsed by the rise of Islamist movements, who have in turn been dismissed as "fanatics", both by the west and some former nationalists. As elections bring one Islamist party after another to power in the Arab world, the US and allies are trying to tame them – on foreign and economic policy, rather than interpretations of sharia. Those that succumb will become "moderates" – the rest will remain "fanatics".

6. Foreign military intervention in the Middle East brings death, destruction and divide and rule

It's scarcely necessary to dig into the archives to work that out. The experience of the last decade is clear enough. Whether it's a full-scale invasion and occupation, such as Iraq, where hundreds of thousands have been killed, or aerial bombardment for regime change under the banner of "protecting civilians" in Libya, where tens of thousands have died, the human and social costs have been catastrophic.And that's been true throughout the baleful history of western involvement in the Middle East. Pathé's silent film of the devastation of Damascus by French colonial forces during the Syrian revolt of 1925 might as well be of Falluja in 2004 or Sirte this autumn – if you ignore the fezzes and pith helmets.

Thirty years later and Port Said looked pretty similar during the Anglo-French invasion of Egypt in 1956 that marked the replacement of the former European colonial states by the US as the dominant power in the region.

This newsreel clip of British troops attacking Suez, invading troops occupying and destroying yet another Arab city, could be Basra or Beirut – it's become such a regular feature of the contemporary world, and a seamless link with the colonial era.

British troops surround hungry crowds in front of the ruins of Port Said, destroyed during the Anglo-French invasion of Egypt in 1956. Photograph: Getty So has the classic imperial tactic of using religious and ethnic divisions to enforce foreign occupation: whether by the Americans in Iraq, the French in colonial Syria and Lebanon or the British more or less wherever they went. The Pathé archive is full of newsreels acclaiming British troops for "keeping the peace" between hostile populations, from Cyprus to Palestine – all the better to keep control.

British troops surround hungry crowds in front of the ruins of Port Said, destroyed during the Anglo-French invasion of Egypt in 1956. Photograph: Getty So has the classic imperial tactic of using religious and ethnic divisions to enforce foreign occupation: whether by the Americans in Iraq, the French in colonial Syria and Lebanon or the British more or less wherever they went. The Pathé archive is full of newsreels acclaiming British troops for "keeping the peace" between hostile populations, from Cyprus to Palestine – all the better to keep control.And now the religious sectarianism and ethnic divisions fostered under the US-British occupation of Iraq have been mobilised by the west's Gulf allies to head off or divert the challenge of the Arab awakening: in the crushing of the Bahrain uprising, the isolation of Shia unrest in Saudi Arabia and the increasingly sectarian conflict in Syria – where foreign intervention could only escalate the killing and deny Syrians control of their own country.

7. Western sponsorship of Palestine's colonisation is a permanent block on normal relations with the Arab world

Israel could not have been created without Britain's 30-year imperial rule in Palestine and its sponsorship of large-scale European Jewish colonisation under the banner of the Balfour declaration of 1917. An independent Palestine, with an overwhelming Palestinian Arab majority, would clearly never have accepted it.That reality is driven home in this Pathé News clip from the time of the Arab revolt against the British mandate in the late 1930s, showing British soldiers rounding up Palestinian "terrorists" in the occupied West Bank towns of Nablus and Tulkarm – just as their Israeli successors do today.

The reason for the security of Jewish settlers, the presenter declares in the clipped, breathless tones of the 1930s voiceover, are "the British troops, ever watchful, ever protective". That relationship broke down after Britain restricted Jewish immigration to Palestine on the eve of the second world war.

Britain's colonial reflex, in Palestine as elsewhere, was always to present itself as "guardian of law and order" against the "threat of rebellion" and "master of the situation" – as in this delusional 1938 newsreel from Jerusalem.

But the original crucial link between western imperial power and the Zionist project became a permanent strategic alliance after the establishment of Israel – throughout the expulsion and dispossession of the Palestinians, multiple wars, 44 years of military occupation and the continuing illegal colonisation of the West Bank and Gaza.

The unconditional nature of that alliance, which remains the pivot of US policy in the Middle East, is one reason why democratically elected Arab governments are likely to find it harder to play patsy to US power than the dictatorial Mubaraks and Gulf monarchs. The Palestinian cause is embedded in Arab and Islamic political culture. Like Britain before it, the US may struggle to remain "master of the situation" in the Middle East.

No comments:

Post a Comment